It is difficult to overstate how exceptional human tissue is. 1 cubic millimeter of the human brain contains ~57,000 cells and 150 million synapses, wired and connected to allow for the utmost precision required for memory, thought and consciousness. A similar size sample of cardiac muscle contains thousands of functionally associated contracting cardiomyocytes, aligned and connected to each other through gap junctions that synchronize electrical impulses across the organ. These structures result from incredibly complex developmental processes that ensure function throughout the lifetime of the organism, while producing and secreting factors that work for the whole system. No synthetic material can come close to this and (so far) there is no manufacturing process that can replicate the complexity at scale.

If we could reliably manufacture human tissue at high margin, we would unlock one of the most valuable materials on Earth: enabling first a high-fidelity validation substrate for the predictions of AI molecular models, and ultimately, the direct application of these tissues as curative therapies. Tissue engineering was founded decades ago to pursue this goal. Yet despite sustained investment, the field has repeatedly encountered fundamental biological and economic limits. Organoids lack the structural organization required for native function and exhibit drift and batch variability that undermine scalability. Single-cell replacement strategies are powerful, but only for a narrow set of indications, and cannot address the broad, high-value applications that require intact, multicellular tissue. Meanwhile, scaffold-based and bioprinting approaches struggle to achieve reproducible native microarchitecture at clinically relevant scale, while decellularized scaffolds face severe challenges in recellularization and standardization.

In practice, the field remains poor at producing true native human tissues.

We believe there are two problems at the core of the plateau tissue engineering has found itself in. First, it has not been able to unchain itself from the need to mechanistically understand morphogenesis before replicating it in the lab. One of the working assumptions is that we must decode the exact (spatial and temporal) sequencing of signals, molecules, and extracellular cues to grow tissues in vitro. The resulting parameter space is impossibly vast, with typical trajectories involving dozens of factors across dozens of timepoints. We have been exploring this space one experiment at a time, guided by scientific intuition and literature precedents. As a result, each effort to produce tissue has demanded its own bespoke protocol, developed through years of trial-and-error by specialized labs. Tissue engineering, so far, has been more akin to a craft than a standardized engineering process.

Second, even when protocols succeed, it is extremely difficult to make unit economics work. Bespoke optimization is slow, with single design-build-test cycles that can take weeks or months. Expert opinion and labor are extremely expensive. Manual protocols are brittle and hardly ever reproducible. This results in exploding costs, trapping tissue engineering at the discovery stage, with academic labs producing proof-of-concepts that cannot be replicated at the volumes, consistency, and costs required for commercialization.

But, what if you didn't need to understand developmental biology to recapitulate it? What if, instead of painstakingly identifying the "right" signals through mechanistic studies, you could use developmental datasets to constrain a tractable parameter space and then let closed-loop computation find what works?

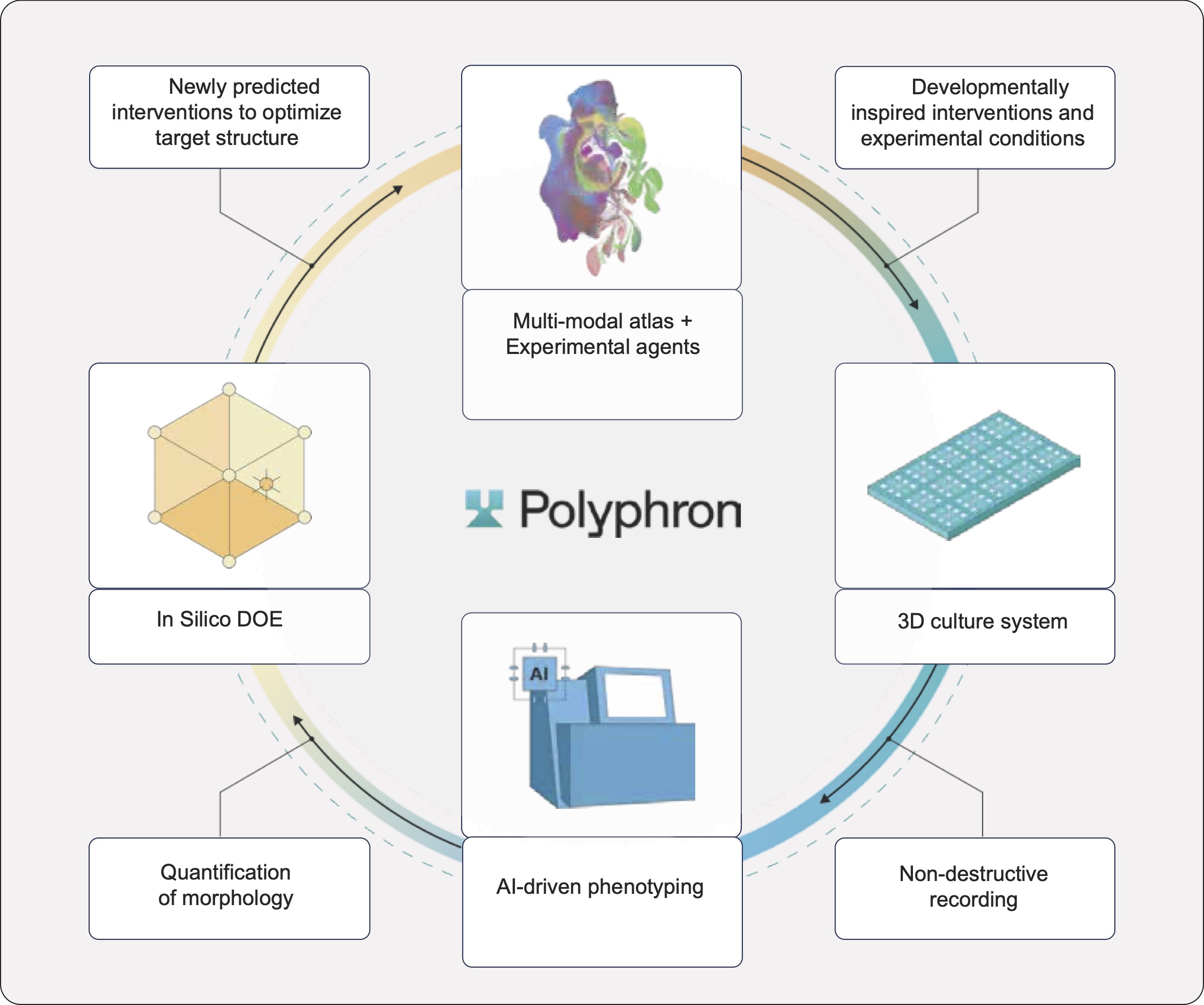

We are building the world's first autonomous tissue foundry to test this hypothesis. The main elements of the foundry (Figure 1) are:

- Atlas-Informed Priors: Candidate interventions (factors, small molecules, matrix components) are identified mining human developmental single cell atlases.

- High-throughput Experimentation: Developmentally-inspired perturbation sets are run across high-throughput 3D iPSC-derived tissue constructs.

- Active Learning: Response to perturbations is recorded non-destructively across the course of the whole experiment. AI-based phenotyping quantifies response to the perturbations and Bayesian optimization is used to in silico design the next round of conditions that can efficiently optimize the target tissue structure.

Polyphron’s timelines are exemplary and iteration cycles are more akin to engineering sprints than a classic biotech discovery process. Every loop closes in weeks, not months. Each iteration generates dense time-series data connecting perturbations to hundreds of constructs and millions of cells. The resulting dataset, growing iteration after iteration, becomes a systematic mapping of how interventions drive tissue structure, across conditions, timepoints, and tissue contexts.

This is the first installment of a two-part series where we illustrate our vision and how we are building a technology to overcome the limitations described above. In this post, we offer an overview of the platform and show how we used it to successfully control a critical structural feature of natural tissue, tissue polarity, across two distinct lineages with minimal retuning. Next, we will produce a study on the unit economics of an autonomous tissue foundry.

Why polarity?

We focus on cell alignment and polarity as our optimization target because polarity is a precondition for higher-order tissue organization as seen in lumens, barriers, and conduction and transport systems across human tissues.

In cortical tissue, neuronal polarity establishes the biological basis for information flow in neural circuits. The excitatory neurons in the cerebral cortex have a highly organized and radial structure, with dendrites oriented towards the pial surface and axons projecting towards the basal one. Disorganized neuronal grafts form aberrant connectivity patterns that disrupt functional circuits and hamper information processing. In cardiac tissue, cardiomyocytes must align to generate coordinated contractile force and support anisotropic electrical conduction. Misaligned grafts risk arrhythmias and poor mechanical integration. Native myocardium achieves substantially higher contractile output from aligned versus disorganized cells.

We set out to test whether our platform could use small molecules to grow highly aligned cortical and cardiac constructs. Functionally, this meant that our closed-loop platform had to target two objectives simultaneously: alignment magnitude (how aligned cells are) and consistency (how consistently aligned across the construct the cells are). Both are required to manufacture functionally active constructs.

Program 1: Controlling excitatory neuron alignment

The cortical program at a glance:

- 2,814 observations across 3 iterations (perturbed constructs + controls)

- >2M cells analyzed

- 24 unique molecules tested at 5 different concentrations

- 2 different seeding densities

- Total duration of the program: 10 weeks

Results by Iteration:

We challenged our platform to autonomously reproduce in vivo-like radial orientation in 3D cortical excitatory neurons in vitro. To do so, we first integrated over 1.2 million single-cell profiles from human developmental datasets, capturing spatiotemporal gene expression trajectories, and distilled ~20,000 genes down to 24 candidate morphogenetic interventions with no manual curation. We further increased the complexity of the search space to include additional design-of-experiments factors (5 titrated concentrations, 2 seeding density), resulting in 212 unique conditions that were tested in replicates on admixtures of excitatory and inhibitory neurons seeded in our 3D experimental set up. We ran three Bayesian optimization iterations, targeting increased median directionality (90° is the max) and reduced MAD (proxies for magnitude and spread respectively) of the excitatory neurons in culture.

Because baseline performance shifted across experimental batches, a universal challenge in biological experiments, we evaluated progress using per-plate control normalization. Each perturbation was compared to controls run on the same plate, on the same day, avoiding plate-associated confounding effects.

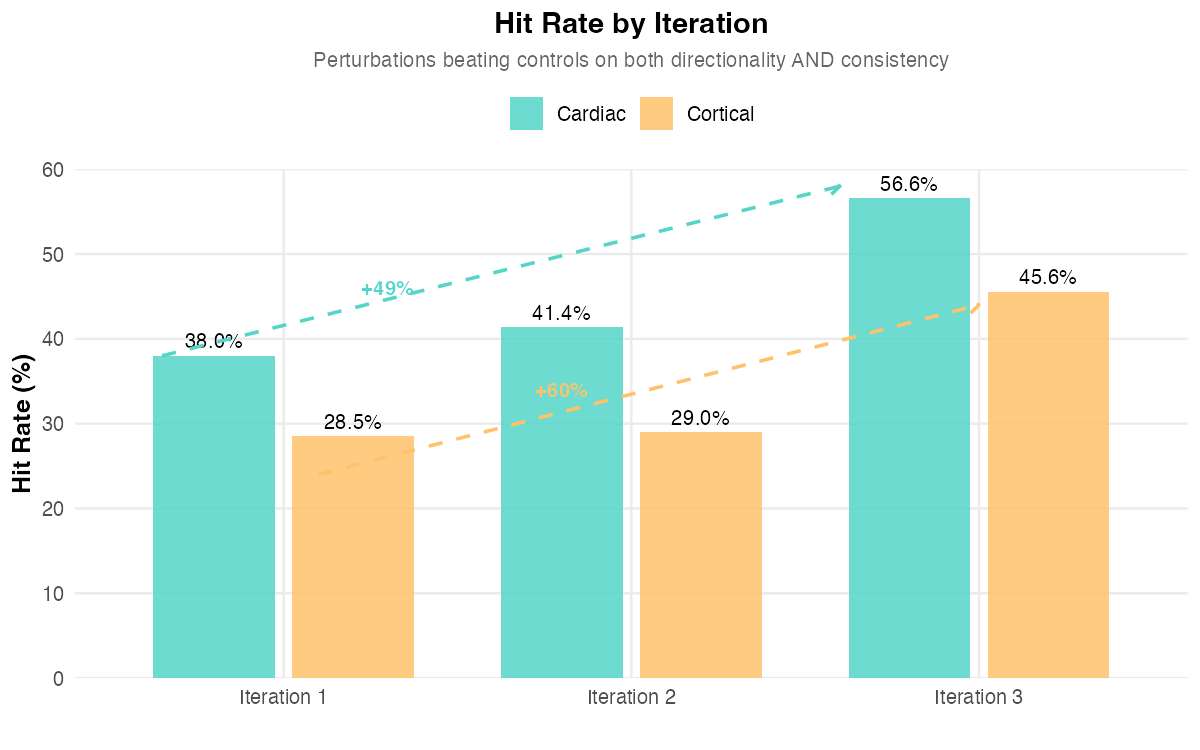

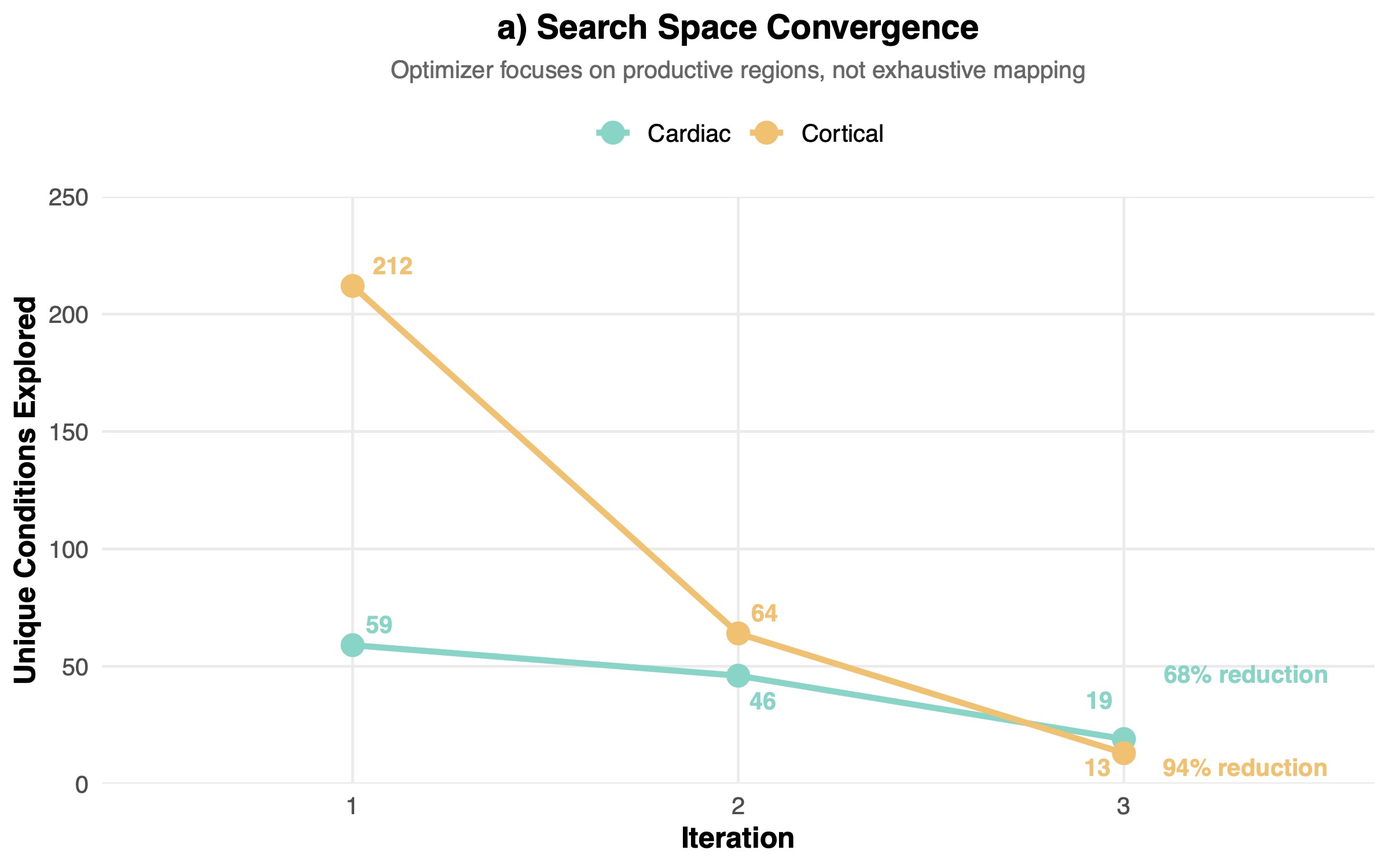

We observed strong convergence from iteration to iteration (64 conditions in Iteration 2; 13 in Iteration 3). By Iteration 3, the optimization loop achieved robust alignment improvements with a marked gain in MAD improvement versus controls (median Δ = +2.60°) and an increased hit rate, the fraction of perturbed constructs exceeding controls on both objectives, (45.6% vs 28.5% in Iteration 1). The top performing experiment achieved 81.9° median directionality versus 49.1° in controls, a substantial improvement in tissue organization. Importantly, only excitatory neurons were affected, proving our platform’s highly-granular cell type specific control.

Program 2: Controlling cardiomyocyte alignment

The cardiac program at a glance:

- 893 observations across 3 iterations

- >900k cells analyzed

- 17 unique molecules tested in pairwise combinations at fixed concentrations

- Total duration of the program: 5 weeks

Results by Iteration:

To test whether the structural control observed in cortical systems generalized to a distinct tissue context, we applied the closed-loop perturbation framework to cardiac differentiation to tune polarity in a similar manner as the neuronal experiments described previously. We seeded iPSC derived cardiomyocytes in our experimental plates. Under baseline cardiac differentiation conditions, cardiomyocytes differentiated efficiently but exhibited limited tissue-level organization, with heterogeneous cell orientation and largely isotropic architecture.

Once again, we ran three Bayesian optimization iterations to optimize cardiomyocyte alignment, using the same optimization function as for the cortical program. We derived 17 unique morphogenic interventions from ~150k cells made public as part of an atlas of the developing human heart. Given the results of the cortical program, where concentrations derived from potency/KD seemed to be the optimal value throughout, we explored the interventions at fixed concentrations.

Across iterations, the hit rate increased from 38% (Iteration 1) to 41.3% (Iteration 2) to 56.56% (Iteration 3). The median perturbation shifted from below-control performance in Iterations 1–2 to above-control performance in Iteration 3. The MAD improvement (Δ = +0.79°) indicates the optimizer found perturbations producing more consistent alignment than untreated controls. The top performing experiment achieved 89.4° median directionality with near-zero variability (vs 81.9° directionality and 7.1° MAD in controls).

Comparative Analysis

Across both programs, we observed the same qualitative signature of effective lab-in-the-loop optimization. The cortical program, with its higher-dimensional search space, showed more dramatic improvement (60% vs 49%) suggesting that neurons might be more responsive to small molecule perturbations than cardiomyocytes (Figure 2). This is in line with the developmental mechanisms driving morphogenesis in the two tissues, given that mechanical forces play a driving role in alignment of the myocardium.

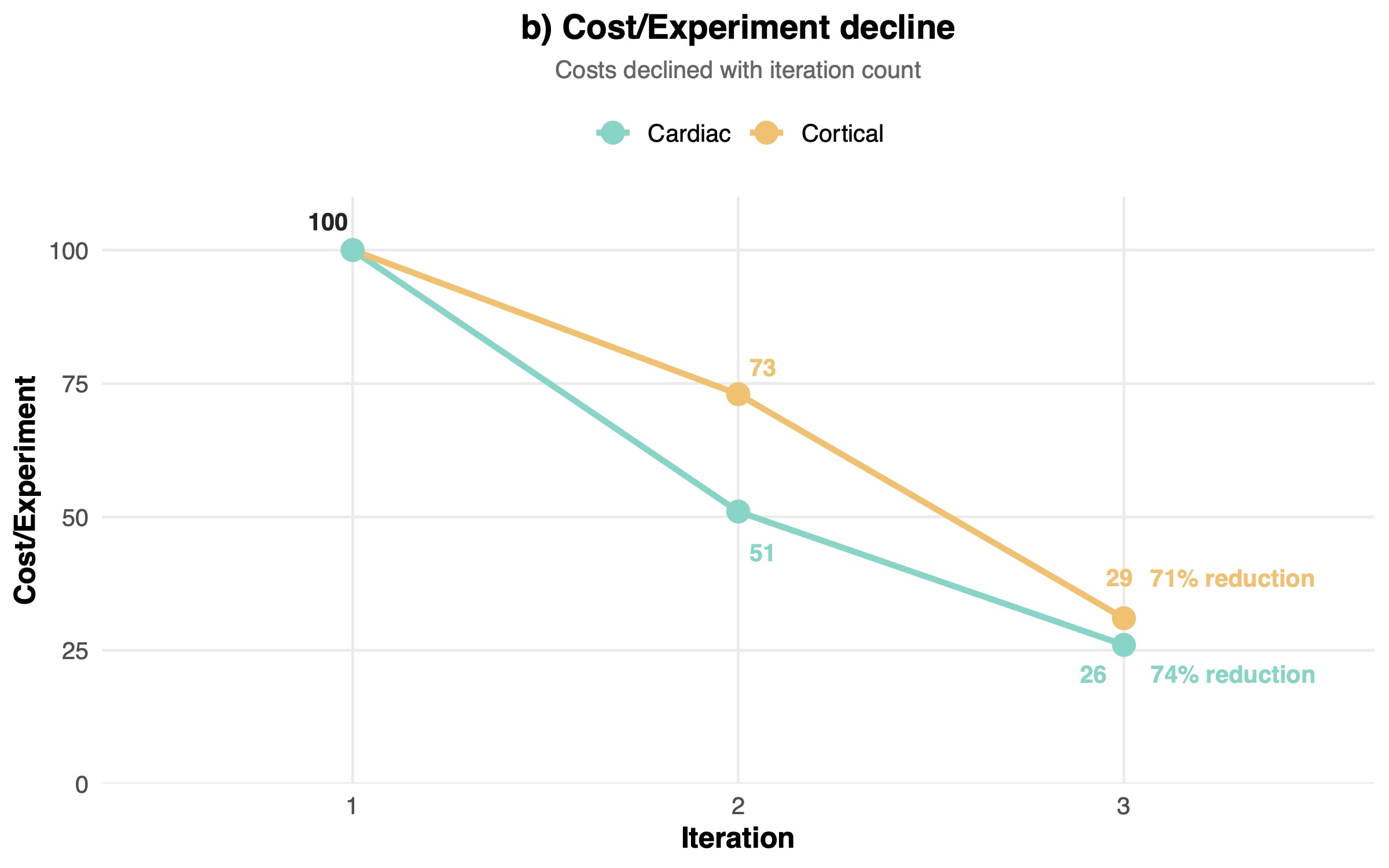

The cortical program also displayed more aggressive convergence, with 94% vs 68% reduction in unique tested conditions (Figure 3a). The aggressive compression in the search space across the two programs highlighted the power of in silico design of experiment approaches for tissue engineering. Notably, given that optimization reduces failed experiments, labor hours per construct, and reagent usage per iteration, costs declined with iteration count. The experimental costs per experiment in dollar terms dropped robustly as we cycled through each iteration: in the cortical program they dropped by 70.7%, in the cardiac program costs dropped by 74.3% (Figure 3b).

These results did not come as a total surprise, given the variable noise levels and batch effects inherent to biological systems. Early rounds cover broad regions of the design space and map the response surface. Later rounds exploit the learned structure, yielding higher fractions of perturbations that outperform baseline controls on both median alignment and variability. In our data, this manifested as broad condition diversity and many underperforming perturbations in the first two iterations, followed by convergence to a focused subset of experiments that reliably matched or exceeded baseline performance.

Despite the low number of iterations and tested compounds, we observed that convergence rate scaled with dimensionality. The higher convergence of the cortical program was consistent with effective active learning in larger search spaces, suggesting that the algorithm gained more information per experiment when there was more information to learn.

Implications and Future Work

With this post, we are not claiming to have solved tissue engineering but these results show that an autonomous tissue foundry is not only technically feasible, but tractable as an engineering and manufacturing system. By closing the loop between high-throughput experimentation, non-destructive phenotyping, and active learning, tissue development shifts from a bespoke, intuition-driven process to a repeatable optimization problem operating on engineering timescales.

This has direct implications for cost, quality, and scalability. Parallelized optimization reduces labor intensity, search-space compression lowers reagent and failure costs, and continuous phenotyping enables real-time quality control rather than end-point inspection. Together, these properties create a clear path to predictable unit economics and reproducible outputs, prerequisites for tissue to become a product rather than a prototype.

Just as importantly, the platform produces the data required for robust quality control. Each construct is accompanied by dense, time-resolved measurements linking inputs to structure and variability, enabling explicit specification of acceptable performance bounds. This transforms tissue manufacturing from an artisanal process into one governed by measurable tolerances.

Near-term future work will focus on increasing biological complexity while preserving this level of control, including symmetry breaking, multicellular organization, and additional functional readouts. These extensions follow directly from the same closed-loop framework demonstrated here.

High-fidelity human tissue also enables applications upstream of therapeutics. As AI molecular design and prediction models improve, experimental validation has become the dominant bottleneck. Native-like tissue produced with controlled variability represents a uniquely powerful validation substrate for AI-driven hypotheses, exceeding the fidelity of organoids and cell-based assays while remaining economically tractable.

Taken together, these results suggest that human tissue can be made specifiable, reproducible, and scalable under engineering constraints.